New rules on the use of mobile phones while driving, do not go far enough and have been labelled a “missed opportunity”, by road safety experts.

The Government has announced it will be illegal to use a hand-held device under virtually any circumstance while driving, but hands-free calls will still be permitted and the potential risks around distracted driving from infotainment systems remains unresolved.

Fleet risk director at Driive Consulting and former fleet manager, Alison Moriarty, said: “While I welcome any changes that reduce distractions to drivers caused by mobile phone use, the proposal does not go far enough.

“It is proven that the physical effects of holding a device are not as much an impairment to concentration as the mental distraction of holding a conversation and this is the same when using hands-free.

“In fact, you are four times more likely to be involved in a collision, resulting in injury, if you are on a call including using hands-free options.”

Shaun Helman, chief scientist for behavioural and data sciences at TRL (Transport Research Laboratory), welcomed the legislation being updated, but believes it could be construed as a “bad thing” by retaining the focus on hand-held devices.

“It reinforces the myth that’s the most important thing,” he said.

There are four types of distraction: manual, visual, auditory and cognitive. Helman explained: “What this law still does is focus on just one of those.

“In that sense, it’s a missed opportunity and it’s maintaining this flawed narrative that, as long as you’re not holding something, you’re safe.”

It was already illegal to text or make a phone call (other than in an emergency) using a hand-held device while driving.

MOBILE PHONE LAW LOOPHOLE

The Government launched a consultation on mobile phone use while driving in October 2020 to close a loophole in the original law.

The law referred to “interactive telecommunication” reflecting how, when it was written in 2003, smartphones were not in existence and mobile devices were used for sending texts or making calls.

It has enabled lawyers to successfully argue that using a phone’s camera while driving does not constitute “interactive telecommunication”.

It was brought to a head in 2019, when a driver had a conviction quashed for filming a crash on his mobile phone.

His lawyers successfully argued that the law only banned the use of mobile phones to speak or communicate while behind the wheel.

Transport secretary Grant Shapps said: “By making it easier to prosecute people illegally using their phone at the wheel, we are ensuring the law is brought into the 21st century.”

Anyone caught using their handheld device while driving will face a £200 fixed penalty notice and six points on their licence.

The Government says drivers will still be able to continue using a device ‘hands-free’ while driving, such as a sat-nav, if it’s secured in a cradle.

However, if police deem that they are not to be in proper control of their vehicle, they can be charged with careless driving.

Moriarty says allowing drivers to still use phones in a cradle, sends the wrong message. “You are condoning them to take their eyes off the road, which can be lethal even for a few seconds,” she said.

“Drivers will, inevitably, continue to scroll through messages and music choices and fail to be in full control of their vehicles.”

DEFINING DISTRACTION

Helman says that one of the problems is that “we don’t really know what’s safe enough”.

A report he co-authored explains that there are rules of thumb, and specific studies that it can cite guidance from, such as research from the National Highways Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) around distractions in the vehicle.

It suggests that any task requiring individual glances away from the road of two seconds or more should not be allowed.

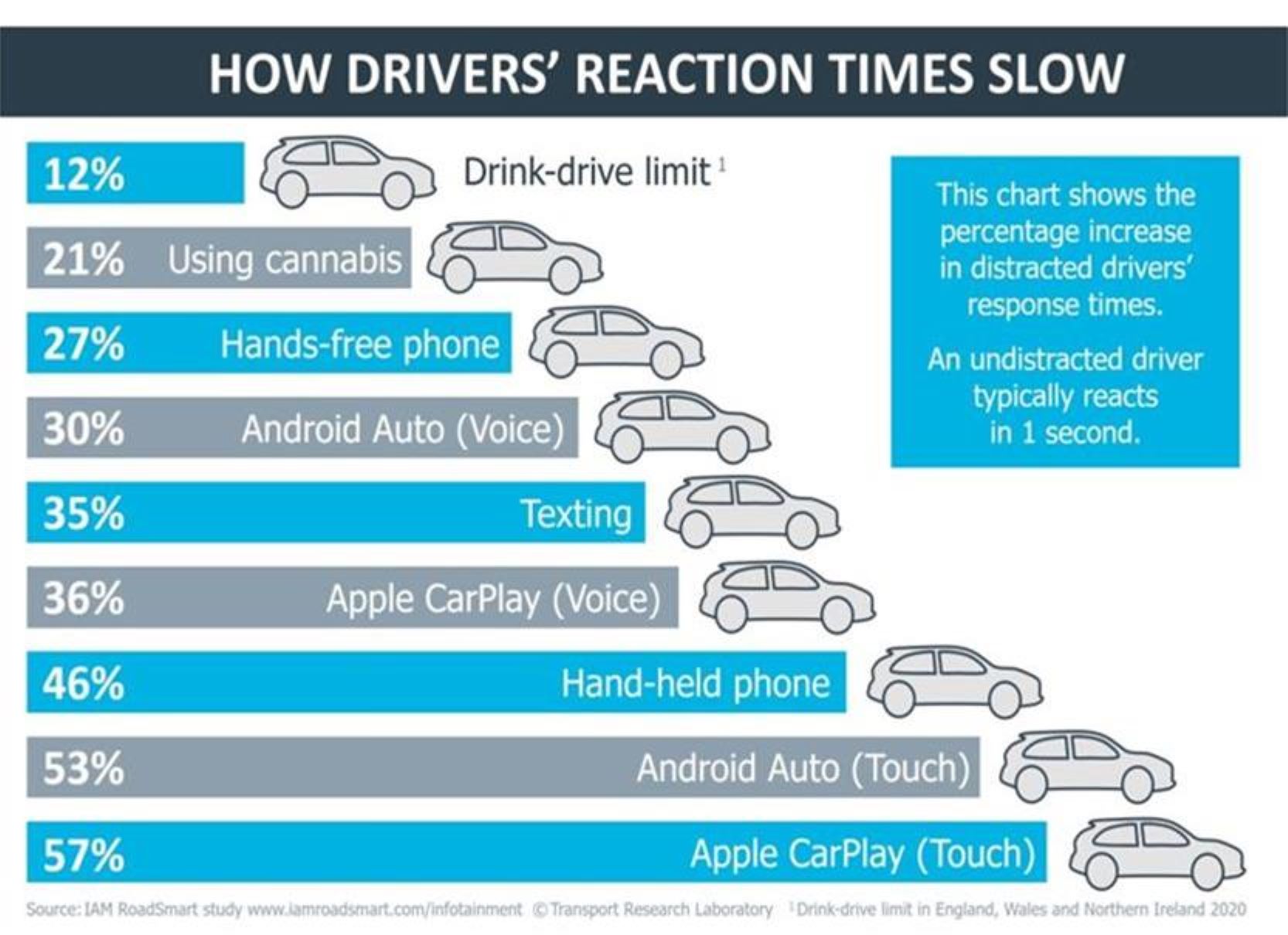

Work from TRL, meanwhile, has shown that response times to sudden events when driving in a simulator are slower with a task that mimics even a hands-free conversation on a phone.

The study found that the slowing of reactions was even greater than that seen when drivers were at the legal alcohol limit for driving.

Helman explained: “There’s an acceptable level (of distraction), but I suspect it probably should be below hands-free phone conversations.”

He also acknowledges that infotainment systems, which provide drivers with increased connectivity and access to apps, are part of the problem.

“There’s a clamouring for the driver’s attention,” he explained, with poor design being a particular problem. “Badly designed interfaces will jar and cause attentional refocusing.”

Research from IAM RoadSmart, published last year, showed that infotainment systems impair reactions times behind the wheel more than alcohol and cannabis use.

The study – undertaken by TRL on behalf of IAM RoadSmart, the FIA and the Rees Jeffreys Road Fund – found that reaction times at motorway speeds increased average stopping distances to between four and five car lengths, drivers took their eyes off the road for as long as 16 seconds while driving, and using touch control resulted in reaction times that were even worse than texting while driving.

OTHER LEGAL ROUTES

Paul Loughlin, a solicitor specialising in motoring law at Stephensons, told Fleet News that the new legislation does not consider other distractions within the vehicle such as infotainment systems or sat-navs or even phones being used as sat-navs.

However, he said: “Taking your attention away from the road for too long while engaging with technology that is fixed to the vehicle in some way can still be extremely dangerous and can still be considered an offence.”

The law does not have a specific offence for those instances, but the offences of careless driving and dangerous driving are often applied where there is clear evidence that a driver is unduly distracted by an in-vehicle function that can lead to the standard of driving falling below that of a competent and careful driver, he explained.

“Careless driving can give rise to a penalty of between three-to-nine penalty points or even a ban from driving,” he added. “A conviction for dangerous driving carries with it a mandatory minimum ban of 12 months together with the risk of a prison sentence.”

Those offences are generally used where there is evidence of bad driving that may or may not lead to an accident, but the police do have the option of deterring a driver from being unduly distracted by an infotainment system by charging them with an offence of ‘not being in proper control of a vehicle’.

“There does not need to be evidence of bad driving in this scenario,” said Loughlin. “This carries a penalty of three points and a fine.”

TESTING OF IN-CAR DEVICES

TRL says what is needed is an approach to policy based on an agreed metric of attention, probably arrived at through a standardised testing approach for any new technologies.

It believes ‘attention testing’ should be akin to ‘emissions testing’ for personal, vehicle and roadside technologies.

By developing attention standards or guidance that manufacturers and software developers can follow when developing in-vehicle technologies and interactive elements, it could encourage a structured approach to assessing interface design.

Similar to Euro NCAP standards for vehicle design, this would encourage the development of safer infotainment systems, it says.

Moriarty agrees. “I think that there needs to be a holistic industry working group set up to mitigate the risks associated with distracted driving. This needs to include the vehicle manufacturers who are including increasingly more infotainment options in vehicles,” she said.

“Any of these systems need to include rigorous safety features to stop drivers accessing them while driving.”

Jason Wakeford, head of campaigns at road safety charity Brake, urged fleets to tighten up their road risk polices.

“We hope fleet managers will now do even more to educate drivers about the risks of using mobile phones,” he said.

ROBUST FLEET POLICIES

Moriarty says fleets need to have robust policies in place so that drivers understand their responsibilities. “Fleet managers should educate drivers and companies should allow drivers to feel comfortable to not take calls while driving,” she said.

Simon Turner, campaign manager for Driving for Better Business, believes the change in the law will force many businesses to look again at their policies for mobile phone use while driving.

“To be compliant, and to ensure the safety of staff, other road users and pedestrians, it’s essential that leaders integrate information surrounding the use of mobile phones into their driving for work policy,” he said.

“Regular checks should be carried out to ensure that all employees have read and understood the guidelines and are complying with them.”

MONITORING DRIVERS

Technology can help. Driver behaviour can be monitored by equipment such as dashcams with a driver-facing camera, says Saul Jeavons, director of road safety consultancy, The Transafe Network.

“The key is to win hearts and minds by educating drivers alongside any technological measures such as blocking apps or dashcams,” he said.

“If drivers understand the dangers, and how things which feel safe can actually be dangerous, they will be less likely to offend.

“As with everything in road safety, there is no single magic bullet, but a combined toolkit of approaches can yield results.”

TTC, a provider of driver training and safety programmes, says best practice is to change driving behaviour overall and ensure that sat-navs are programmed before drivers set off, and that all other potential distractions such as music choice are avoided while at the wheel.

“This change in laws is coming at a time when we already have a significant number of drivers approaching a ban due to an accumulation of points,” said Andy Wheeler, business development director at TTC Group. “The coming introduction will see these drivers at serious risk from being removed from the roads for a single, if serious, infraction.”

Brake supports the families of road crash victims, including those who have had lives “torn apart” as a result of someone not paying proper attention when driving, says Wakeford.

“The temptation of using a phone can never be worth someone’s life,” he added.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.