More than a third of companies do not have a clear strategy to reduce carbon emissions from their light commercial vehicle (LCV) fleets, according to a new Fleet News survey sponsored by DriveElectric.

Regardless of the merits of implementing an electrification strategy well ahead of the 2030 deadline on the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles, the absence of a carbon reduction plan effectively means these organisations are failing to deploy fuel cost controls in the face of accelerating petrol and diesel pump prices.

The survey of UK businesses, carried out in March, found that 65% of respondents have robust plans to transition their fleet away from diesel to full electric (EV) and plug-in hybrid (PHEV), although their current fleet profiles are still heavily weighted towards internal combustion engine (ICE) vans.

On average, 87% of vans operated by survey respondents are diesel, although full battery electric is the second highest proportion at 6%, noticeably ahead of PHEV at 1.5%.

In the LCV sector, fleets appear far more willing to leapfrog PHEV to go direct to full electric, buoyed, in part, by the wider range of electric vans on the market compared with PHEV options.

In the LCV sector, fleets appear far more willing to leapfrog PHEV to go direct to full electric, buoyed, in part, by the wider range of electric vans on the market compared with PHEV options.

The pace of change is accelerating, with electric accounting for 21% of forward orders, although diesel still dominates with a 73% share.

While a plethora of electric product exists in the medium-size van market, large vans are still underserved by electric, with the handful of available products offering a range which doesn’t meet most fleets’ needs.

British Gas, for example, has been forced to continue buying some diesel product until suitable electric alternatives come to market.

Its head of fleet Steve Winter says:

“Due to the lack of suitable large electric vans that work on our total cost of ownership (TCO) model, we have taken the decision to have a number of diesel VW Crafter vans on a short lease.”

Supply issues are furthering hampering fleets’ efforts to move away from diesel to electric, with semiconductor shortages pushing order times out beyond 12 months in many cases. The situation is unlikely to ease until 2024.

“My simple calculation is that if they (vehicle manufacturers) are already nine-to-12 months behind, just to catch up they’ve got to run double for the next two years,” ISS UK fleet manager Duncan Webb told viewers of March’s ‘Fleet News at 10’ webinar.

“It’s not going away this year or next year; it’s probably 2024 to resolve.”

However, there is a bright light on the horizon for electric, according to National Grid fleet manager Lorna McAtear. She says:

“With a limited supply of components, where are they going to focus? We’re starting to see the focus accelerating the net zero transition.”

That will boost the one-in-10 fleets which are planning a complete transition to EV or PHEV vans by 2025, while a further 46% are looking to move everything across by 2030.

A large proportion (44%) will still be running some diesel vans up to and past the 2030 deadline and will continue their transitions for the subsequent few years as they gradually de-fleet those vehicles. Meanwhile, a handful of small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) believe they will “never” run a fully electric van fleet.

With city regions compelled to tackle air quality issues, clean air zones (CAZs) are widely expected to evolve into zero emission zones (ZEZs), which would restrict the ability of any non-EV fleet to operate without facing huge fines.

With city regions compelled to tackle air quality issues, clean air zones (CAZs) are widely expected to evolve into zero emission zones (ZEZs), which would restrict the ability of any non-EV fleet to operate without facing huge fines.

Oxford became the first authority to trial a ZEZ in February covering a number of streets in the city centre. A wider ZEZ incorporating the whole of the centre is scheduled for launch in 2023, subject to public consultation. Other councils are watching the project with interest.

Transitioning to electric is not without its hurdles, although the biggest corporates have been able to manage with minimum operational impact.

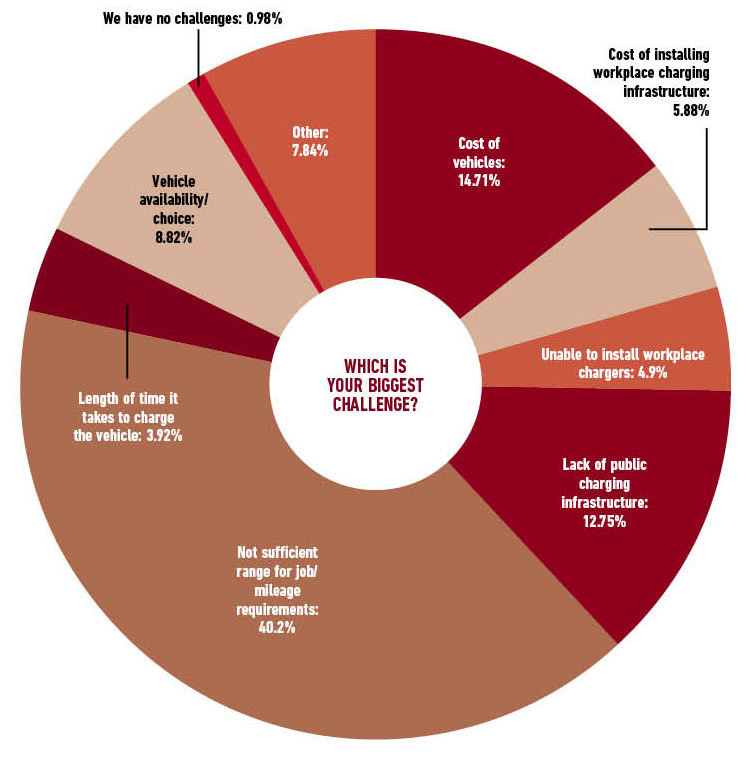

Range and public charging are the two biggest issues identified by fleets, highlighted by 62% and 53% respectively, followed by cost of vehicles (52%) and – with the current shortages – vehicle availability (46%).

But, when asked about their single biggest issue, range was the overwhelming concern of 40% of survey respondents, followed by cost (15%).

To alleviate range anxieties, businesses need to undergo journey mapping and data analysis to establish which vehicles within their fleets are most suitable to convert to electric. The findings are often a surprise, with companies frequently discovering that a reasonable proportion of vehicles fall within scope.

Cost is another misnomer, with the higher P11D pricing putting some fleets off the investment. However, it is vital that businesses utilities TCO modelling to show the full picture.

Electric vehicles may have a higher price, but they cost less in fuel, although the recent increases in the price of electricity have narrowed the gap – figures from some fleets reveal that fuel now accounts for 30% of the TCO saving where previously it was as much as 50%.

Fleet engineer at British Gas James Rooney says:

“The fuel saving isn’t as good as everyone thinks because electricity isn’t that cheap, especially since it recently doubled in price.”

He adds: “The major savings are on maintenance and downtimes. The service, maintenance and repair (SMR) cost is less than half of an ICE vehicle. We also save on our spare fleet because the vehicles don’t break down, so we don’t need to run a surplus. And we are also getting 2,000-3,000 more miles per tyre.”

Several fleets have also started to calculate the cost to the business in terms of brand image or lost work of not investing in an EV transition. With many Government contract tenders requiring proof of environmental credentials, inactivity is no longer an option for many businesses.

The third single biggest issue identified by fleets was the lack of a public charging infrastructure (12.75%) – crucial as half of fleets say some of their electric vans are charged on the public network.

This has been acknowledged by the Government in its EV Infrastructure Strategy, where it accepted that the pace of roll-out had been “too slow”, adding that the public charging network “often lets people down” in terms of reliability and transparency of charging fees.

It has committed substantial funds to speed up the nationwide installation of charge points, with a £950 million Rapid Charging Fund to support the roll-out of at least 6,000 high-powered chargers across England’s strategic road network by 2035. It is also aiming to have at least six high-powered charge points at each motorway service area by the end of next year.

The Government has also launched a ‘Geospatial Commission’ to explore how location data can be better utilised to support planning and delivery of charge points by local authorities.

These authorities are now obligated to develop and implement charge point strategies that meet the transition to zero emission targets.

In addition, new legislation will come into effect this summer designed to improve the public experience of using charge points.

In addition, new legislation will come into effect this summer designed to improve the public experience of using charge points.

The regulations will be overseen and monitored by a public body and will mandate reliability standards and ensure drivers can access real-time information about charge points and compare prices. It will also support fleets with the introduction of payment roaming.

Public charging will be of particular importance to staff who are unable to install a home charge point – Department for Transport data suggests almost a quarter of households do not have off-road parking facilities.

However, this proportion rises to almost 40% when considering the available space required to accommodate the larger dimensions of a van, according to data compiled by Field Dynamics for the Association of Fleet Professionals (AFP) kerbside charging project.

And, if the homeowner wishes to park their car on the drive overnight, it means 56% of households would not be able to charge a van at home.

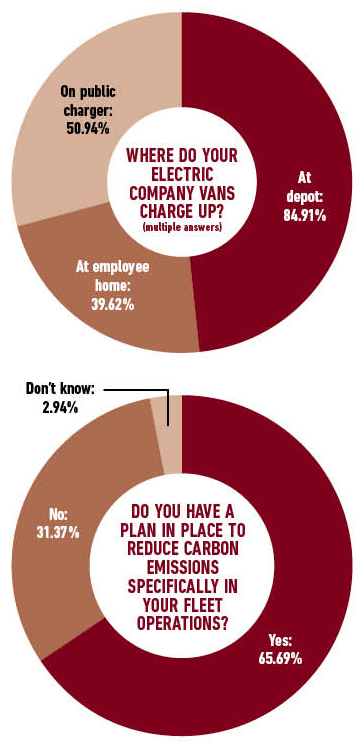

Almost four-in-10 companies say some of their vans are charged at home, although the vast majority – 85% – have EVs that are charged partly at the depot. In total, 40% of fleets solely charge their vans at depot, but just 6% say their drivers only charge at home or on public chargers. The rest use a mix of charging options.

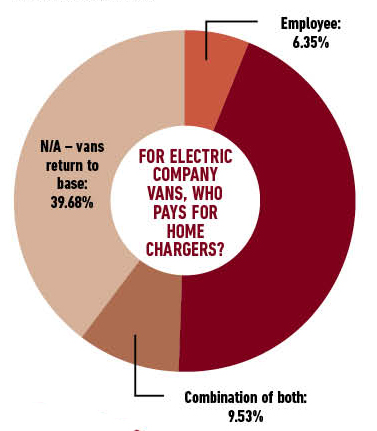

The vast majority of companies (74%) pay for the installation of a home charger for their van drivers; for 16%, it is a combination of company and employee, while 10% require the employee to fund the cost.

Most companies (61%) have installed chargers at their workplace and have deployed a range of power outputs: 42% have 7kW, 44% have 22kW, 17% have 50kW and the rest either are unsure or indicate they have a mix of 11kW, 24kW and 32kW.

For most fleets, 7kW options are sufficient to charge vehicles overnight or during the day; more powerful chargers enable rapid charging for highly utilised vans, or act as a safeguard should someone forget to charge up.

Of the 39% of companies yet to begin installation of workplace chargers, 65% intend to start the process soon, but 35% have no current plans to introduce them.

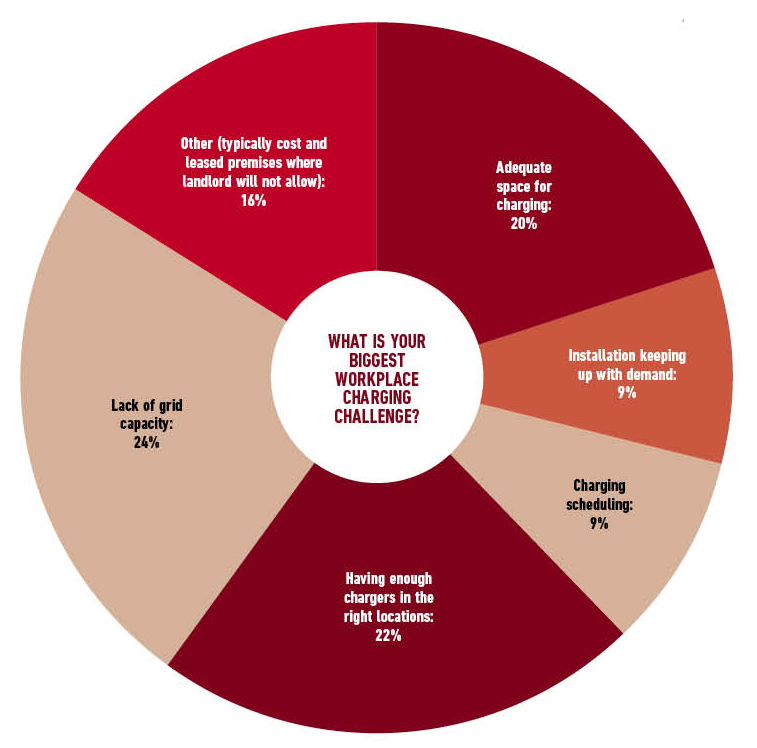

Three challenges stand out when it comes to the installation of workplace charging, according to survey respondents.

Three challenges stand out when it comes to the installation of workplace charging, according to survey respondents.

Almost a quarter (24%) of fleets say the biggest issue is the lack of local grid capacity which requires substantial investment in upgrading local substations; 22% have issues about placing their chargers in the right locations at their depots; 20% simply do not have adequate space to accommodate chargers.

Less prominent, yet still among the challenges for some fleets, are considerations such as scheduling to ensure the right vehicles are charged at the right time; future-proofing as the number of EVs on fleet grows; cost of installation; and gaining permissions from landlords to install charge points on leased premises.

The challenges – and opportunities – presenting by the transition to an electric fleet underline the changing role of fleet decision-makers.

As James Rooney puts it: “Fleet managers have gone from being niche procurement managers to strategists. They are key to a company’s ESG (environment, social and governance) policies, which means they no longer work in a silo; they are cross-department, engaging stakeholders from across the business.”

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.