New technology that could dramatically reduce real-world emissions of diesel engines could be just two years away.

Researchers at Loughborough University have created a world-first technology, and they claim to have had interest from a number of manufacturers who want to fit it to their diesel cars.

Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) emissions are higher from diesel engines than from petrol engines, and have required vehicle manufacturers to introduce exhaust after-treatment systems to clean up the level of pollutants from diesel to comply with European legislation.

While all new vehicles sold comply with the latest emissions requirements in the official tests, they have been criticised for producing much higher amounts of NOx in real-world driving that exceed EU limits.

They came under greater scrutiny in 2015 after it was revealed Volkswagen had included a so-called ‘defeat device’ on its diesel cars in the US to produce lower NOx emissions for official tests than were achievable in real-world driving.

The problem of NOx on local air pollution has prompted London to introduce a supplementary fee for older vehicles in the congestion charge zone, while other cities and urban areas have been considering their own strategies to improve air quality (see page 36).

Now, almost all new diesel vehicles are fitted with a selective catalytic reduction (SCR) system to try to remove NOx produced by combustion. This system uses AdBlue, or diesel exhaust fluid, to safely provide the ammonia required to reduce NOx to harmless nitrogen and water.

One problem with AdBlue is it functions best at high exhaust temperatures, typically in excess of 250ºC. Therefore, the SCR does not necessarily operate at all engine conditions, for example, during short, stop-start commutes in urban areas or on construction sites.

And the use of AdBlue at these problematic lower temperatures can result in severe exhaust blockages and subsequent engine damage, which means it’s often deployed in lower quantities and NOx emissions are increased.

Ammonia creation and conversion technology (ACCT) has been created by academics from Loughborough University’s School of Mechanical, Electrical and Manufacturing Engineering. It effectively increases the capacity of existing after-treatment systems.

ACCT is an AdBlue conversion technology that uses waste energy to modify AdBlue to work effectively at these lower exhaust temperatures.

By greatly extending the temperature range at which SCR systems can operate, the new technology significantly enhances existing NOx reduction systems. It is the only technology of its kind, according to Loughborough University.

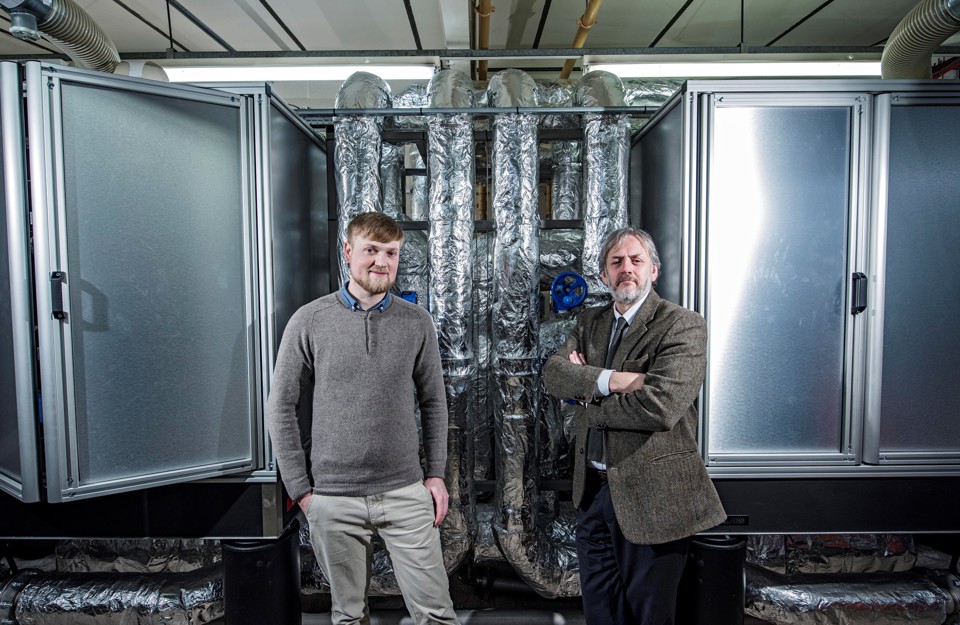

Loughborough professor Graham Hargrave, an internationally acclaimed expert on the optimisation of combustion engines, developed the technology with research associate Jonathan Wilson (both pictured).

“We are all familiar with the ‘cold start’, where diesel vehicles spew out plumes of toxic emissions before their catalytic systems are up to temperature and able to work effectively,” said Hargrave.

“Unfortunately, with many vehicles doing short, stop-start journeys, such as buses and construction vehicles, many engines never reach the optimal temperature required for the SCR systems to operate efficiently. The result is excessive NOx being released into the urban environment, especially in large cities.

“Our system enables the SCR systems to work at much lower temperatures – as low as 60ºC. This means the NOx reduction system remains active through the whole driving cycle, leading to significant reductions in tailpipe emissions.”

Initially meant for HGVs, Wilson said the technology is applicable to any diesel engine, and a number of car manufacturers have been in touch to investigate adopting ACCT.

On cold and wet days, many cars’ current SCR systems are also challenged by surface water preventing them reaching optimum temperature, meaning that NOx emissions could be higher than the prescribed limits.

Wilson said: “We would prefer to see ACCT given widespread use rather than being exclusive to one vehicle manufacturer. The cost of the system would be relatively inexpensive.”

He added that it could also make diesel-hybrid powertrains more feasible, with those facing a particular challenge from reduced opportunity to reach high temperatures in urban driving, as the electric motor is programmed to run alone for short distances.

The development from Loughborough University comes as Bosch claims it has achieved a “breakthrough” in diesel technology by dramtically cutting NOx emissions.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.