Fleets are reluctant to switch their vans from diesel to electric, citing cost, vehicle range and regulations as major barriers to uptake.

With the pace of van electrification not matching that seen in the car sector, which has been driven by the company car market, the Government has given operators more time to adapt.

With the sale of new petrol and diesel cars ending from 2030, vans with an internal combustion engine (ICE) will be allowed to be sold until 2035, alongside full hybrids and plug-in hybrid vans.

The majority of van fleets, spoken to by Fleet News, say that they are unlikely to delay their van fleet electrification plans as a result of the Government announcement.

However, the reality is many fleets have no plans at all to electrify their vans, irrespective of the new deadline, according to new research.

It suggests fleet ambitions are falling short of Government targets, with a range of measures needed to driver greater interest.

Figures show that there were approximately 80,000 electric vans on UK roads at the start of the year, out of total 4.7 million light commercial vehicles (LCVs) – just 1.6% of the UK van fleet.

Manufacturers were targeted with ensuring 10% of all new van registrations were zero emission last year, increasing to 16% this year, with an updated zero emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate increasing flexibility for manufacturers to balance the annual targets against each other and avoid fines by selling more battery electric vehicles (BEVs) in later years.

The latest new van sales data from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) reveals adoption rates are falling short of the mandated figure, despite a healthy increase in uptake.

“Regulatory barriers remain a key blocker for van fleet decarbonisation,” Toby Poston, BVRLA

Demand for new battery electric vans in May was up by 50% to 1,731 units – the seventh successive month of rising demand.

However, they represented just 7.6% of the overall market in the month and 8.2% year-to-date – half the 16% share mandated for 2025.

Paul Hollick, chair of the Association of Fleet Professionals (AFP), told Fleet News: “Company car electrification has been powered in large part by tax advantages such as reductions in benefit in kind and road fund licence.

“In a matter of a few short years, these advantages have meant that today’s default company car choice is electric.

“While we’re unlikely to see any moves this generous directed at the van sector, there do need to be inducements that create demand momentum around the electric van market.”

He does not believe that supply side changes to the ZEV mandate will generate the kind of impetus required and instead is urging the Government to revisit ideas outlined in the Zero Emission Van Plan, which the AFP produced in partnership with the British Vehicle Rental and Leasing Association (BVRLA) and others last year.

“These include grants, improved charging and reduced regulatory barriers – all of which could help to create much greater fleet enthusiasm,” he said.

No plans to adopt electric vans

New research from the Road Haulage Association (RHA) suggests that more than a third (39%) of van operators are already operating electric vans or plan to have them on their fleets within the next five years.

However, more than half (56%) told the RHA that they have no plans in place to introduce electric vans, with lack of range and high cost cited as the main barriers to preventing their deployment (see below).

Source:RHA

Electric van plans differ according to fleet size, with fewer than a third (32%) of respondents operating 100-plus vehicles saying they had no plans in place to switch to the zero-emission alternative.

Two-in five (41%) already had electric vans on their fleet, with two-thirds (66%) expected to be operating them within five years.

Almost one-third (32%) of fleets operating 100-plus vehicles have no plans to adopt electric vans.

For fleets operating between 25-99 vehicles, just 7% – fewer than one-in-15 fleets – are currently operating electric vans, with that set to increase to more than a third (36%) within the next five years.

More than half (57%) of operators within this fleet size said they were not planning to replace their diesel vans with electric alternatives.

For even smaller operators (5-24 vans), almost three-quarters (72%) said they have no plans to deploy electric vans, with only one-in-five (22%) expected to be operating electric vans within the next five years.

Biggest barriers to van fleet electrification

Lorna McAtear, vice chair at the AFP and head of fleet at National Grid, told Fleet News that battery range is the biggest blocker for operators.

“Many cannot or are unwilling to change their operations, which means many fleet managers are still after an ‘ideal solution’,” she said.

“If manufacturers produced (electric) off-road 4x4s and 3.5-tonne panel vans with a real-world 250-300-mile range and towing capability, the transition would be happening now.

“It is because the commercial vehicles being produced can’t meet those requirements and mean too many compromises in operational practice that fleets can’t transition yet.

“There are a limited number of compromises to operations that can be made.”

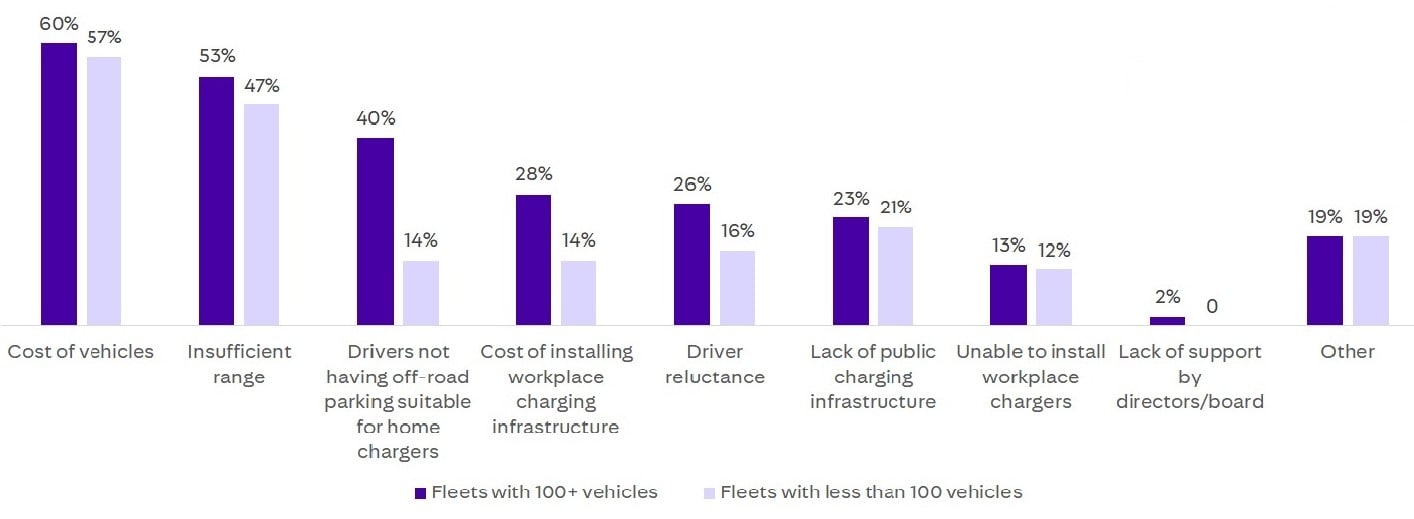

Previous Fleet News research revealed that, for fleets with 100-plus vehicles, the biggest barrier to van electrification – cited by almost two-thirds (60%) of fleets – is the cost of vehicles (see below).

Source: Fleet News

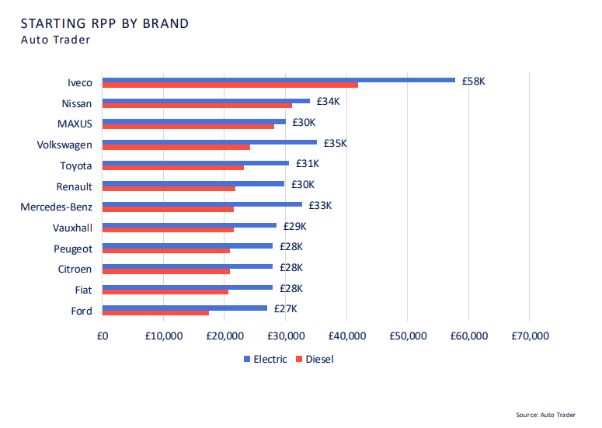

A Vauxhall Vivaro 120PS L1 diesel, for example, has a P11D price of £28,640, while the Vivaro Electric L1 with the larger 75kW battery is almost £14,000 more at £44,602.

Online marketplace data from Auto Trader shows the cost of new electric vans are as much as £20,000 more than diesel vans, with the most expensive Iveco model costing £58,000.

However, when comparing running costs, using the Fleet News ‘Van Running Costs’ online tool, the electric van works out marginally cheaper over five years/100,000 miles at 42.39 pence per mile (ppm) versus 43.88ppm for the diesel equivalent, based on fuel and service, maintenance and repair (SMR) costs, as well as vehicle depreciation.

Furthermore, with manufacturers wanting to increase EV market share to meet Government targets, there is the opportunity to negotiate discount on product.

Auto Trader found that van makers are applying discounts of as much as 26% to new vans (see below).

Fleet News research found the insufficient range electric vans could travel between charging as the next biggest barrier to adoption for more than half (53%) of fleets operating 100-plus vehicles.

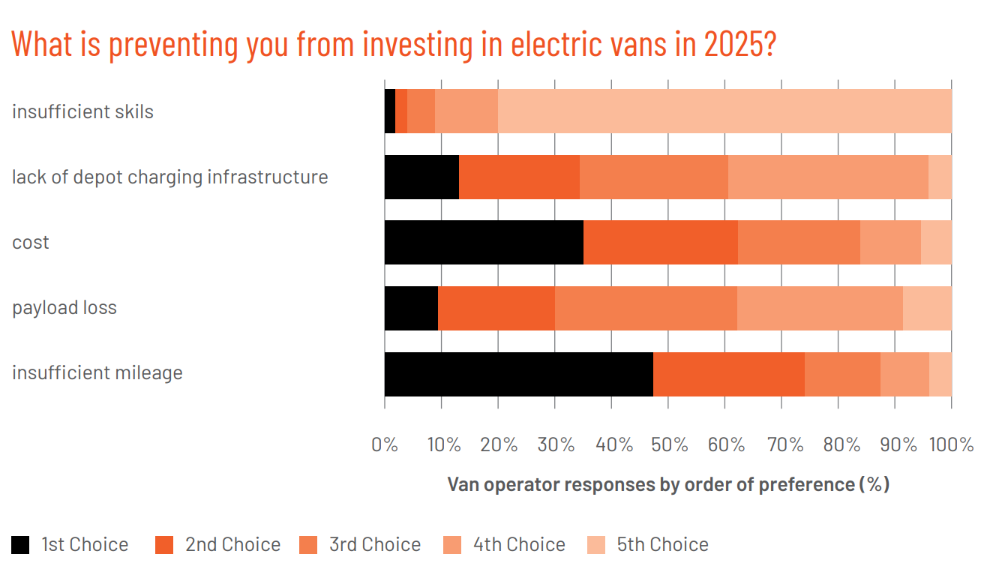

That was echoed by the RHA research, which also found a lack of range (47%) and high cost (35%) the biggest barriers to preventing the deployment of electric vans.

Payload loss issues were ranked as the most significant barrier by just 9% of van operators, with a lack of depot charging infrastructure cited by 13%.

However, these issues were of a higher importance when van operator second choice rankings are also taken into consideration – increasing to 30% and 34%, respectively.

“If you have a battery that is 30% smaller and lighter, but has 50% more range, then you can immediately overcome many of the reasons that currently prevents fleets from transitioning to EV,” said Simon Simmons, LCV consultant at Alphabet (GB).

“Most van fleets expect at least 200-250 miles, with a payload, on a full charge before they can seriously consider it as a viable and cost-effective alternative.

“Therefore, the pressure is on manufacturers to find solutions and capitalise on the technology, which should unlock the potential by the end of the decade.”

Range of measures required to unlock electric van adoption

The Government announced earlier this year that fleets would continue to benefit from up to £5,000 off an electric van after the plug-in grant was extended until April 2026.

The cash incentive was due to end in April of this year, but it is benefitting, in part, from £120 million in Government funding that will see the grant remain at the same level, offering up to £2,500 when buying a small van up to 2.5 tonnes and up to £5,000 for larger van up to 4.25 tonnes.

The Department for Transport (DfT) has also introduced greater licence flexibility for electric vehicles, with new rules for heavier electric vans, bringing them in line with their lighter petrol and diesel counterparts.

The changes, which were first announced in February and came into force on June 10, enable standard category B licence holders to drive zero-emission vehicles up to 4.25 tonnes, broadening the flexibility to cover all vehicle types, beyond goods vans.

Accounting for the additional weight of the vehicle’s batteries, the rule change applies to vans, minibuses, SUVs, trucks, and any vehicle that can be driven up to 3.5 tonnes if they are petrol and diesel.

The additional five-hour training requirement for drivers was also removed along with changes to towing allowances for zero-emission vehicles weighing up to 4.25 tonnes.

You are now able to tow a trailer as long as the maximum authorised mass (MAM) of the vehicle and trailer combination does not exceed 7,000kg.

For example, if your vehicle has a MAM of 4,250kg, then the MAM of your trailer is limited to 2,750kg. The MAM of the trailer must never exceed 3,500kg.

If you passed your category B driving test before January 1, 1997, you can drive vehicle and trailer combinations up to 8,250kg.

Further regulations around the operation of 4.25 tonne electric vans, including those related to annual vehicle testing, drivers’ hours and tachographs, and speed limiter devices, remained unresolved.

The BVRLA, in coalition with Zero Emission Van Plan partners, including the AFP, continues to call for this red tape to be eliminated.

“Regulatory barriers remain a key blocker for van fleet decarbonisation, alongside the lack of fiscal support and concerns over charging,” said Toby Poston, chief executive of the BVRLA. “Government knows the levers that need to be pulled.”

James Rooney, head of road fleet at Network Rail, told Fleet News that making the rules the same for 4.25-tonne electric vans as they are for 3.5-tonne diesel vans was “fundamental” to the powertrain’s success.

Around 3,000 of Network Rail’s vehicles – a third of the fleet – is made up of large vans, which he says are impossible to switch to electric without changes to the rules.

“If you take a 3.5 tonne electric van, you haven’t got the payload... or they don’t come with a big enough battery, and if you take 4.25-tonne (electric van) with current legislation, none of us are able to comply with those additional regulations,” he explained.

Ford told Fleet News it supporting calls for the rules to be the same for electric vans up to 4.25 tonnes as those for LCVs up to 3.5 tonnes.

It also recommends applying the same changes to electric M2 minibuses, by extending the scope to 4.25t vehicles derived from a vehicle category N1 or N2 and converted into a minibus

With vans fleets looking at one potentially two replacement cycles prior to the 2035 diesel deadline, the need for additional action from Government grows, while fleets are being urged not to be tempted to ‘kick the can down the road’.

Hollick said: “Fleets will be able to potentially electrify more gradually and, in doing so, hopefully take advantage of better technology and lower costs as new models come to market over time. But they can’t afford to pause the entire process.”

Simmons concluded: “Even though the changes won’t come into effect for vans for 10 years, fleet operators shouldn’t be sitting back; they should continue to push ahead with their plans to transition their fleet in-line with their renewal cycles or age of the vehicle.”

Taken from the first quarterly edition of Fleet News IQ.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.